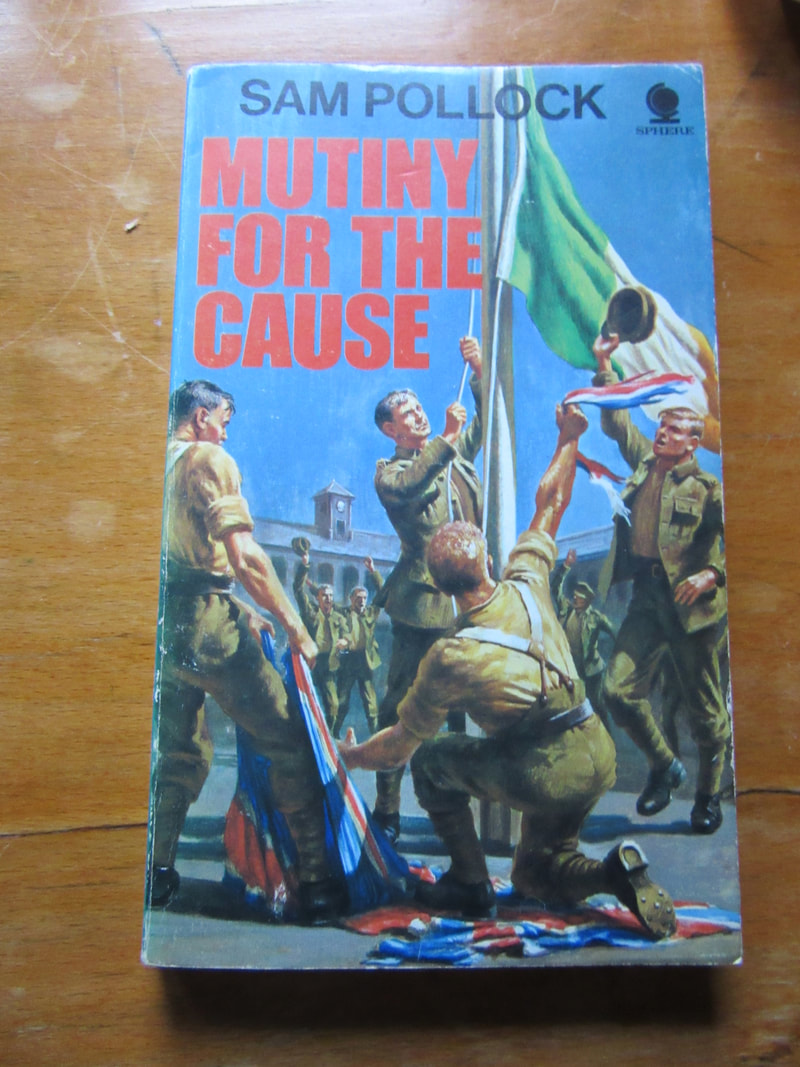

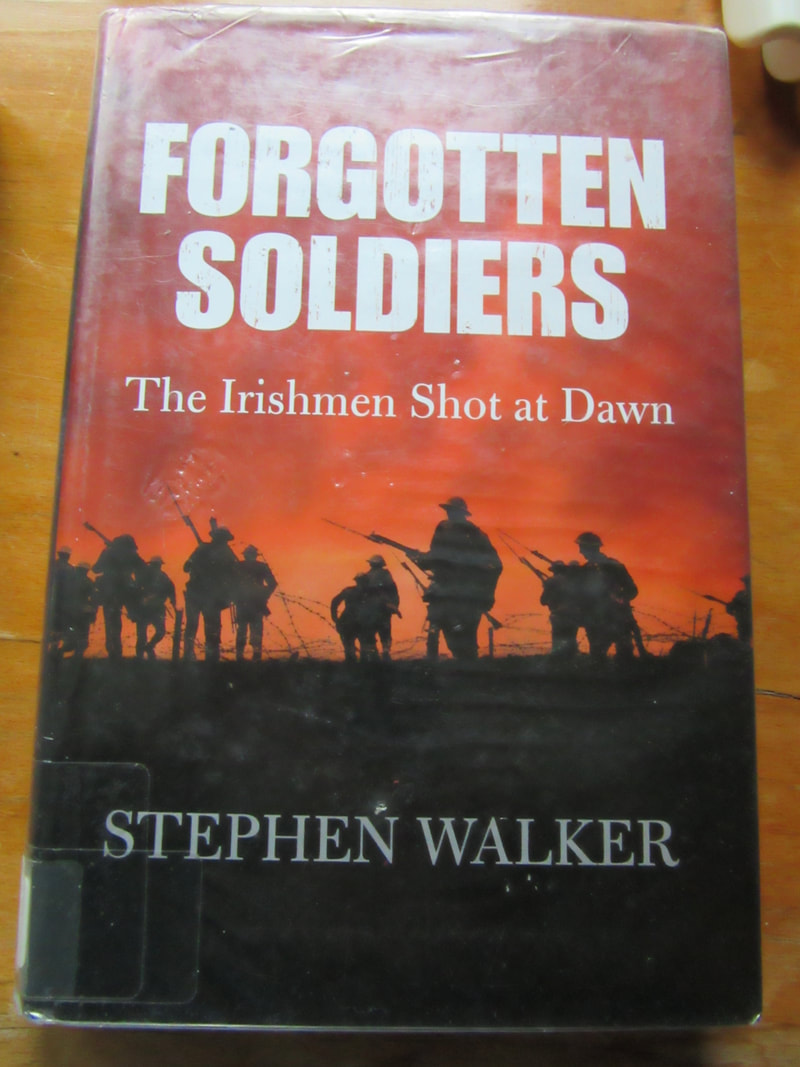

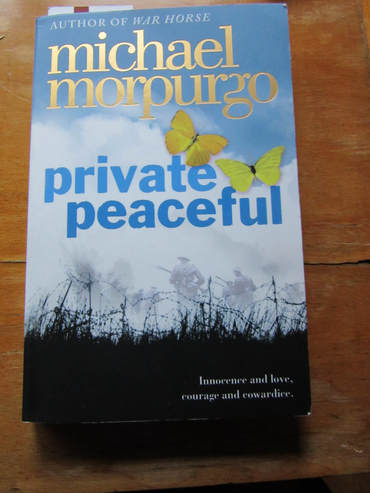

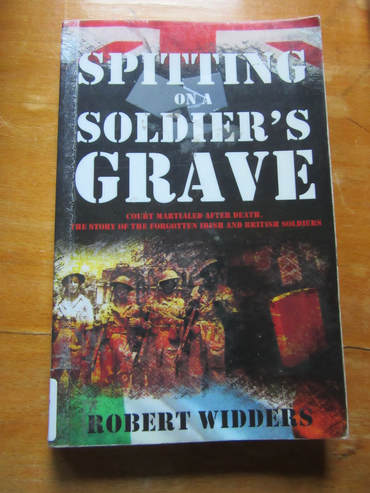

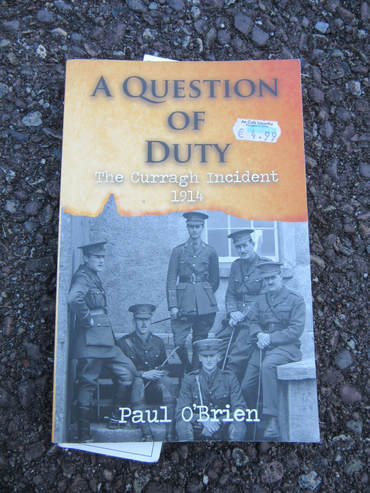

| A tweet from Irish History Links on Thursday reminded that it was 98 years since the mutiny by the Connaught Rangers in India My education of these events was prompted by a headstone in Castlehyde Cemetery near the banks of the River Blackwater, commemorating Patrick McGrath. I had first learned of this event at the annual window sale of history/local books in the Cancer Society shop on Castle Street, where I purchased Mutiny For The Cause, by Sam Pollock. The book had rested on my bookshelf for a year or more. My encounter with Patrick McGrath led to the book being taken from the shelf. My education as to what happened in India in 1920 started and led to bit of a trail about treatment of soldiers disobeying orders. The Connaught Rangers in Jullundur and Solon refused to soldier for the British King because of the actions of the Black & Tans against Irish people. It was a peaceful action – a refusal to work, until after mess closing one night and discussions as to rumour that fellow protestors in Jullundur had been killed, those at Solon sought to break into the munitions store to retrieve their guns – resulting in death of one protestor (Smith in book; Smythe on Wikipedia; Smythe on memorial at Glasnevin, and Pte Peter Sears who depending on the sources was a protestor or was caught by a stray bullet. One soldier died while being held for trial, Private Miranda. James Daly, born in Ballymote, Co. Galway but from Tyrrellspass, Co. Westmeath, the leader of the attack on munitions store, was sentenced to death at court martial hearing. He died by firing squad on 2nd November, 1920. A crowd of more than 6,000 attended the return of Daly’s body to Tyrrellspass in October 1970. The ceremonies, held shortly before the 50th anniversary of his execution, elevated Daly to an equal of the greatest heroes of the republican movement. The Irish flag that draped Daly’s coffin had previously lain on the coffin of Terence MacSwiney, the lord mayor of Cork who died on hunger strike in October 1920. In a speech at Daly’s graveside, Old IRA representative Thomas Malone identified Daly’s sacrifice with the republican goal of a 32-county republic: Mutiny For The Cause led to a period of books on soldier executions. First was a reread- ‘For much of the last century the detail of how hundreds of British soldiers were executed has been a state secret. It is only in recent years that the details of the courts martial and the executions have become public. The story marks one of the most controversial chapters in British military history, and the emotion and pain that surround the men’s deaths. The long-running campaign to obtain pardons for them has clearly pricked the national consciousness in Britain and in Ireland. Twenty five were pardoned in 2006 by the UK Government. In 2001, the Canadian Government spoke of the 23 Canadian soldiers executed in World War I, including James Wilson: ‘To give these 23 soldiers a dignity that is their due, and to provide closure to the families, as Minister of Veterans’ Affairs, and on behalf of the Government of Canada, I wish to express my deep sorrow at their loss of life, not because of what they did or didn’t do, but because they too lie in foreign fields where “poppies blow amid the crosses, row and row.” While they came from different regions of Canada, they volunteered to serve their country in its citizen army, and the hardships they endured prior to their offences will be unrecorded and unremembered no more.’ Michael Marpugo was a favourite of our then ten year old. Many books have been read and audio books heard. When I heard of the play Private Peaceful then coming to the Everyman Palace, the book was purchased and read in a day – one possible example of why a soldier might be executed by his own side. Life intervened and I was unable to get to the Everyman so that remains on the list to be seen. Next up, compliments of the library, was Robert Widders’ Spitting on a Soldier’s Grave which told of those in the Irish Army who deserted to join the British Army to fight in World War II and how they were ostracised by the government here. ‘After the war, the Irish government court-martialled these men en masse and in abstentia. Under Fianna Fáil Taoiseach (or prime minister) Eamon de Valera, the men were formally dismissed from the Irish Army and stripped of all pay and pension rights. The government also circulated a list of 4,983 names and addresses, entitled, the “List of personnel of the Defence Forces dismissed for desertion in time of National Emergency.” The aim was to prevent those men from finding work by banning them for seven years from any paid employment paid by State or public funds.’ Paul O’Brien’s book on The Curragh Incident, or The Curragh Mutiny, A Question of Duty, soon followed on the reading list. Dealing with 1914 when officers in the Army refused to follow orders to prepare for possible action in Ulster against Protestants who were arming themselves in anticipation of defence of the Union of Ireland with Great Britain. You might not find it odd that none of the Officers met the same fate as James Daly – or even Patrick McGrath’s period of hard labour on the Isle of Wight. | Mutiny For The Cause – Sam Pollock (1969) Intro “My dearest Mother, I take this opportunity of writing to you to let you know the dreadful news, that I am to be shot on Tuesday morning, the 1st of November. What harm, it is all for Ireland. I am not afraid to die, but it thinking of you I am. That is all: if you will be happy on earth I will be happy in Heaven. I am ready to meet my doom. The priest is with me when needed so you need not worry over me… I am the only one of 62 of us to be put out of this World, but I am ready to die” Private Jim Daly, leader of the Mutiny P34 onwards – Wellington Barracks, Jullundur “But that summer”[1920]”the men of The Connaught Rangers had to endure worse than the Turkish bath conditions prevailing in the bungalows. In the sweltering heat of the plains of India the British Army normally completed all its parades and exercises in the early hours – between the hours of 6 and 8 a.m., before the sun had climbed to a height which made outside activity a torture and a danger to health. But in June, 1920, the men of The Connaughts had been required to undergo a series of vigorous exercises in daylight hours during which even a brisk walk reduced a soldier’s drill jacket to a sweat-soaked rag. ………. It was suspected by some of the men that this spell of Active Service conditions was deliberately designed to keep them out of mischief – maybe even to weary them beyond the stage at which they might react violently to the news from Ireland; the news of the doings of the Black and Tans. In the event the sufferings imposed on the Rangers – unnecessary sufferings even in the strictest military terms one of the officers was later to agree – aggravated their rage when word came to them of what was being done to their fellow-countrymen at home……. ….It was at the nightly sessions in the battalion Wet Canteen that stories of such happenings,”[Balck and Tan actions]”with the much-thumbed letters from home that backed them, were passed from man to man. The stories and the letters circulated with the beer, each inflaming the effects of the other…. …Sunday, June 27, 1920……That Sunday evening Private Joe Hawes from County Clare sat at a table in a corner apart from the regular schools with four friends: Paddy Sweeney, Stephen Lally, Paddy Gogarty and William Daly. None of the five friends was a member of a Boozing School, being only occasional and moderate drinkers. All around them the air was filled with violent language….as to indignation of the deeds of the Tans about which they’d heard from home or read about in the letters of others. Vengeance was denounced against the perpetrators of the outrages…… None of the shouting that evening that evening was done byHawes and his friends, Quietly they sat in the corner over beer, and quietly they listened to Joe Hawes, the leading spirit of the group, as he urged them that something could be done about what was happening in Ireland. At that time India too, though mainly by passive resistance had begun her struggle for freedom and independence. The year before – in 1919 – a British general, Dyer, had ordered his troops to open fire on a crowd of men, women and children peacefully demonstrating at Amritsar, and over three hundred had died, immediately, that is.; hundreds more probably died later, of those left lying wounded and uncared for on the ground. The Connaught Rangers had had no part in that affair – the troops who obeyed General Dyer’s order were, in fact, Indians. But the Irish battalion was a unit of the British forces in India, and this was a point made by Joe Hawes as he talked with his four comrades. The Connaught Rangers were doing in India, said Joe, the same job that English regiments were doing in Ireland – holding down the people. Did they want to go on doing it? He personally had made up his mind no longer to serve England’s king in that capacity, or any other, until British forces were withdrawn from Ireland. The next day, Monday morning, he intended to go to the guardroom and tell the guard commander that he refused to solider, and ask to be put inside.’Volunteering for the guardroom’ was once a common enough gesture of defiance or protest by British soldiers, usually when under the influence of drink. But, as has been said, Hawes and his four companions were all moderate drinkers, so it was not the case of beer talking. Fired by his eloquence and example, and feeling aggrieved by the news from Ireland which they’d talked about many times, his friends agreed to support and emulate his gesture…. …Early on Monday morning….One man, William Daly, allowed himself to be persuaded, for the time being, that their proposed action would be useless, but the other four – Hawes, Sweeney, Gogarty and Lally – were undeterred. The quartet presented themselves at the guardroom at eight o’clock that morning, and Joe Hawes addressed the corporal of the guard….’In protest’, he said,’against British atrocities in Ireland, we refuse to soldier any longer in the service of the king’ P49 – after Commanding Officer, Colonel Deacon had spoken to the 35 soldiers who now formed the mutiny “It was evident from the expression on some of the men’s faces that the colonel’s plea had impressed them. Joe Hawes stepped forward. ‘Colonel’, he said – and to address his C.O. in that way, and not as ‘Sir’, was presumptuous for a British private soldier in those days – ‘all those honours,’ said Hawes, ‘on The Connaughts’ flag were for England. Not a one of them was for poor old Ireland, and it’ll be the greatest honour of them all.’” Whether this speech of Hawes’ would have by itself have nullified the effect of the colonel’s address, we do not know. Other words, not so loudly spoken by the battalion’s adjunct, who was one of the officers present, may have been more decisive. The adjutant was apparently convinced that the colonel had won – that the men would accept his offer. ‘When the men return to their bungalows’, he muttered to the R.S.M., ‘see that Hawes is put under arrest.’ Softly as he spoke, he was overheard by Private Coman, a man from Tipperary who was one of the thirty-five. Immediately Coman shouted :’Never mind putting Hawes in the guardroom! We’re all going there.’ And turning to his comrades, he commanded: ‘Left turn, lads! Back to the guardroom – quick march!’ And regimental to the last, smartly and in perfect order and step, the volunteers wheeled into the guardroom, and back behind the grill. P65 “In their measures for the security of arms, and in nearly every other activity – guard-mounting, opening and closing of the canteen, and in the daily parade which was still held – the mutineers punctiliously clung to the regiment’s traditional discipline, and to the traditional ceremonial routine. There was, however, one departure from the latter. At sundown every evening, it had been the custom to lower the Union Jack on the flagstaff before the guardroom, re-hoisting it at Reveille. The committee decided that the lowering even temporarily, of the tricolour might be misimterpreted as a sign of surrender. All the night – which ended the first day of the mutiny – the green-white-and-gold flag flew high above the barracks at Jullundur.” P96 “it will be recalled that on the day following the impressive protest led by Jim Daly at Solon, he, with the the other occupants of the hut above which flew the tricolour, had consented to hand over their rifles and ammunition, which were then stored in the magazine under guard……. The mutineers’ rifles and ammunition having been handed in, the rest of the day passed without incident. Outside their bungalow, the men who had refused to soldier mixed freely with those who had remained loyal, when the latter were not on parade…….the policy adopted by the officers of the Rangers there seems to have been like Brer Rabbit to ‘lie low and say nuthin’’….. At dinner in the officers’ mess in Solon that night, a rumour reached the company commander, perhaps through a mess waiter or someone else in touch with the men – that an attempt was to be made by the mutineers to break open the magazine and recover their arms. The magazine, it will be remembered, was guarded by a detachment of bandsmen under their sergeant, all Englishmen, but on hearing this rumour, the company commander ordered the guard to be strengthened and command of it to be taken over by two junior officers armed with revolvers, which they were not to hesitate to use, if attacked. Curiously, at the time, when the rumour reached the officers’ mess, it was unfounded. Daly was fixed in his determination to abide by a policy of non-violence, especially thanks to his outstanding qualities of leadership, he was firmly in control of his followers. Then rumour once more intervened. Just before the canteen closed that night, around 10 p.m., it began to be whispered among the men drinking there, that terrible things had happened at Jullundur. There had been, it was said, another Amritsar massacre, with the victims this time the mutineers of The Connaught Rangers. English troops had marched in, the story ran, and had ruthlessly mowed down Joe Hawes and hundreds of other men who had protested, with machine guns. Were they going to sit there helpless, some of Daly’s men asked, until the same happened to them? Why should they not break into the magazine and, recovering their arms, die like soldiers selling their lives dearly, not like dumb cattle led to the slaughter? Some who urged this course had, no doubt, drunk quite a few pints of beer that evening, but Jim Daly….was a total abstainer. He told the men he was going to keep his promise to Father Baker, and that in any case, the rumours were probably wild exaggerations. One of his followers sneered. Was their leader afraid? For all his strength of mind, Jim Daly was too young, and too high-spirited, to remain unmoved by such a remark. He’d show them. He’d lead them to the magazine, if they’d follow. Twenty-seven men volunteered to take part in the operation, which Jim Daly remained level-headed enough to insist should be soberly planned, and carried out after a reconnaissance…. By the light of the moon they could see that the guard had been heavily strengthened. In place of the lone sentry, several men, with rifles to the ready, were patrolling around the magazine, and others could be observed lying on the flat roof, also armed and ready to repel an attack. But Daly had now committed himself and was not the man to draw back…Determined that his followers should know what they were up against, he stressed the strength of the guard and its obvious preparedness to fire on any aggressor. No matter, said the volunteers – it was only bluff and they’d call it. Daly instructed them to be ready to rush the magazine at midnight. Bayonets, the only arms they had, would be carried. At midnight, with naked bayonets in their hands, the party deployed at the foot of the slope, and, led by Daly, advanced in line uphill…….A challenge from one of the magazine patrol rang out: ‘Halt! Who goes there?’ Again, some guile might have been more effective, but it was not Jim Daly’s way. ‘I am’, he oddly replied, ‘Jim Daly of Tyrrellspass, Westmeath. Hand over our rifles, and there’ll be no trouble.’ ‘If you advance another step,’ called an officer from the roof of the magazine, ‘we’ll fire.’ While he spoke the cassocked figure of a priest came running from the direction of the men’s quarters. It was Father Baker, to whom Daly had given his promise. But before Father Baker could reach the attackers, Jim Daly had spoken. ‘Come on, boys!’ he shouted; ‘charge for Ireland!’ And, clearly marked by the white shirt he wore, contrasting with the army ‘grey-backs’ of the others, he ran up the slope towards the magazine, waving on the men behind with his drawn bayonet. A volley of shots rang out from the roof, and two of the attackers fell to the ground. At that moment Father Baker reached them, and with outspread arms restrained Daly and his followers from advancing further. ‘Cease fire!’ the priest shouted towards the magazine, and then turning to Daly told him that any more bloodshed would be on his head……. Then Father Baker pointing to the two figures lying prone on the ground, urged that they be taken immediately to the medical hut. One of them was already dead. The second, John Egan, had been shot through the lung but lived to nurse that scar, with others received at Mons and Ypres, at his home in County Mayo. The man killed outright was Private Smith.” P101 “In an interview with an Irish newspaper in 1952 Joe Hawes stated that the shots were fired by two officers, Walsh and McSweeny. He also stated that a second man killed, Sears, was not one of the Mutineers but was hit by a stray bullet whilst walking towards his quarters some way away.” P103 – when Mutineers held in cells awaited trial “But an occasional cigarette was not enough to stave off the disease induced by bad and inadequate food. Several of The Rangers were struck down by dysentery, and were reduced to almost skeletons by the time they were brought to trial. ‘I wonder,’ said one of them later, ‘that the witnesses for the prosecution were able to identify some of us. I didn’t recognize myself, when I looked in the glass.’ One man, an Englishman called Miranda, died of dysentery in Dagshai. ‘He wasn’t an Irishman,’ the same informant remarked; ‘But he was a true comrade. God rest his soul!’” P118 “Daly lies buried in the Simla hills in Dagshai military cemetery – grave number 340.” |

|

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFrom Cork. SUBSCRIBE

Unless otherwise specifically stated, all photographs and text are the property of www.readingthesigns.weebly.com - such work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution - ShareAlike 4.0 International Licence

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

Blogs I Read & LinksThought & Comment

Head Rambles For the Fainthearted Bock The Robber Póló Rogha Gabriel Patrick Comerford Sentence First Felicity Hayes-McCoy 140 characters is usually enough Johnny Fallon Sunny Spells That’s How The Light Gets In See That Tea and a Peach Buildings & Things Past Built Dublin Come Here To Me Holy Well vox hiberionacum Pilgrimage in Medieval Ireland Liminal Entwinings 53degrees Ciara Meehan The Irish Aesthete Líníocht Ireland in History Day By Day Archiseek Buildings of Ireland Irish War Memorials ReYndr Abandoned Ireland The Standing Stone Time Travel Ireland Stair na hÉireann Myles Dungan Archaeouplands Wide & Convenient Streets The Irish Story Enda O’Flaherty Cork Archive Magazine Our City, Our Town West Cork History Cork’s War of Independence Cork Historical Records Rebel Cork’s Fighting Story 40 Shades of Life in Cork Roaringwater Journal |