“My dearest Mother, I take this opportunity of writing to you to let you know the dreadful news, that I am to be shot on Tuesday morning, the 1st of November. What harm, it is all for Ireland. I am not afraid to die, but it thinking of you I am. That is all: if you will be happy on earth I will be happy in Heaven. I am ready to meet my doom. The priest is with me when needed so you need not worry over me… I am the only one of 62 of us to be put out of this World, but I am ready to die”

Private Jim Daly, leader of the Mutiny

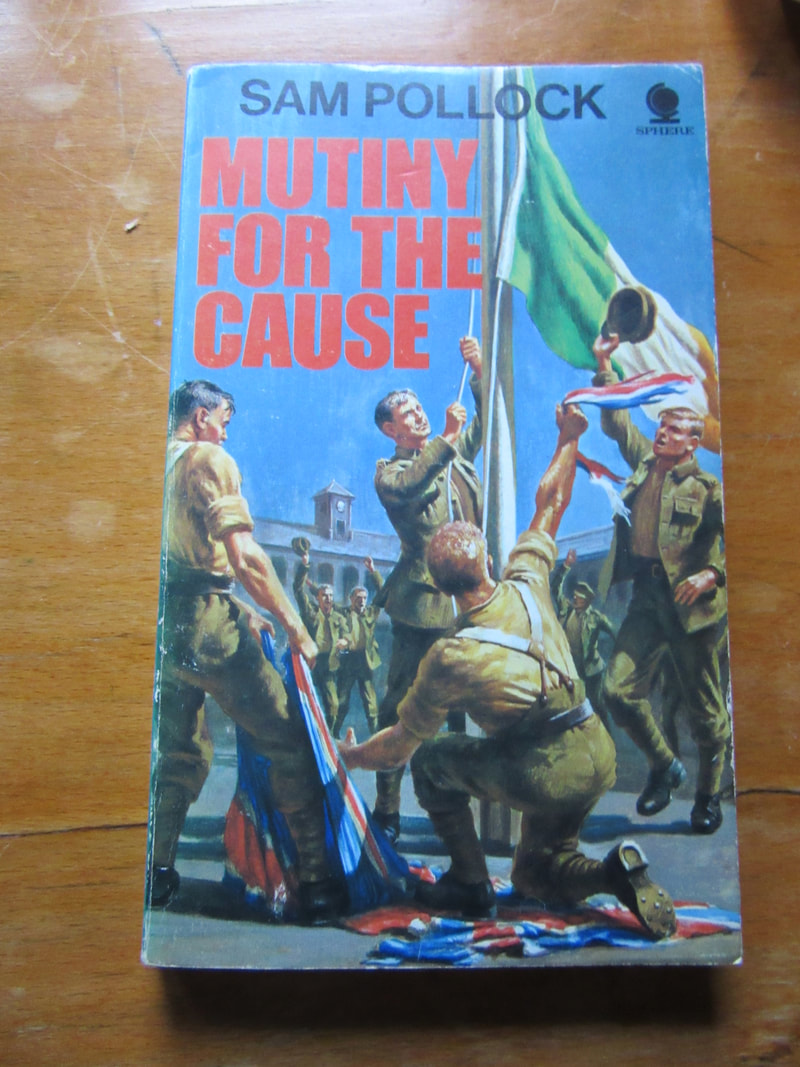

Mutiny For The Cause – Sam Pollock (1969)

Growing up I would have learned of Kevin Barry, the former Belvedere student who was due to sit an exam as part of his U.C.D. Medical Studies but participated in an I.R.A. attack, was captured, court-martialled and hanged. Years ago, I would have heard the song sung by Paul Robeson, Leonard Cohen and others.

It was much more recently that I learned of James Daly.

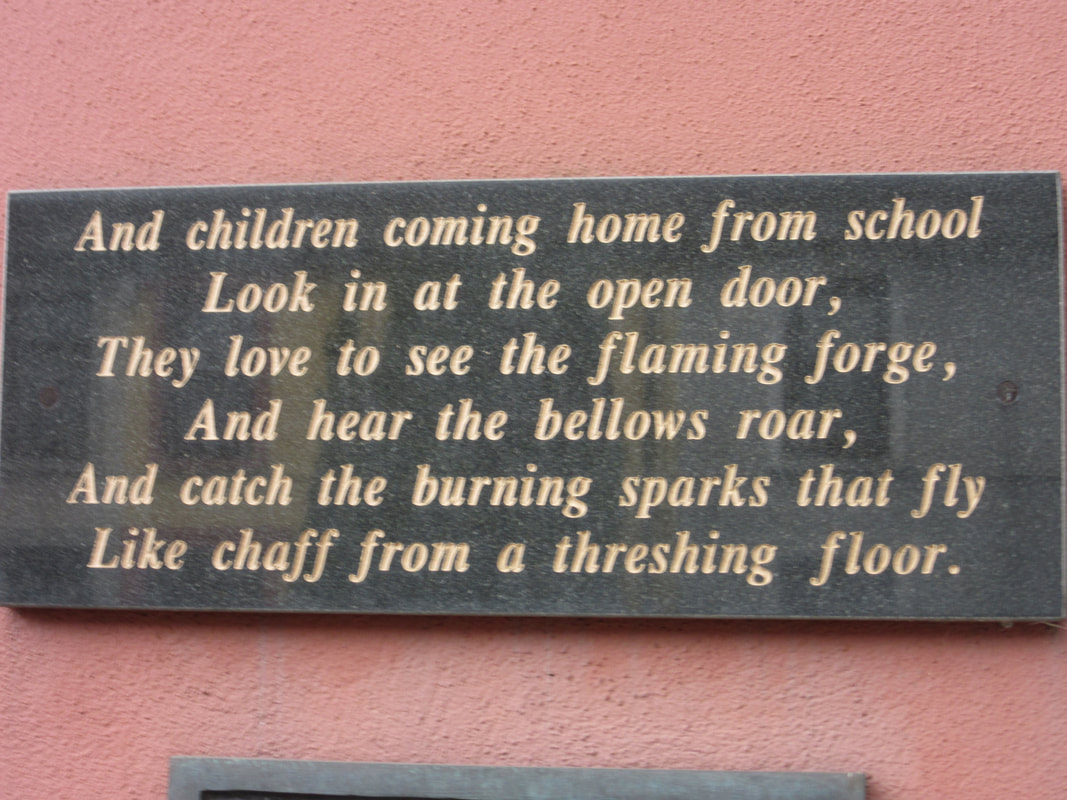

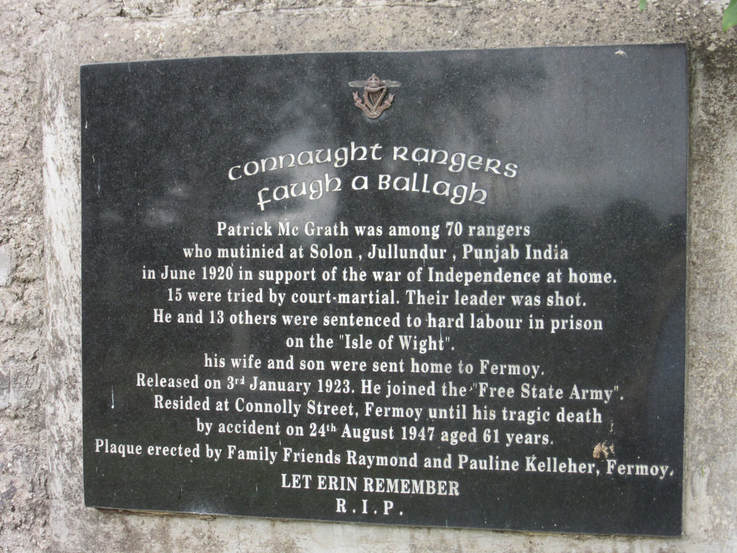

He was a member of the Connaught Rangers who refused to soldier when they heard of the treatment of Irish men and women at the hands of the Black & Tans. Patrick McGrath, a colleague of his from India, lies in Castlehyde Cemetery. His headstone prompted my reading of the Indian Mutiny.

James Daly led a group of the Connaught Rangers in an attempt to regain their guns which they had handed over. Two soldiers died. As leader, James Daly was court-martialled and executed.

Last month, I had to travel from Dublin to Roscommon so I availed of the opportunity to travel the old main road west and make a visit to Tyrellspass and leave one of my stones on the grave of James Daly.

| | |